“You wake up. The room is spinning very gently round your head.

Or at least it would be if you could see it which you can’t.”(1)

That whimsical description is the introduction to 1978 The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (HG2G), a text-based game rendition of Douglas Adam’s timeless classic. And it only gets better…

In today’s article, we set out to rediscover the fun of storytelling. And is there a better place to start than the annals of text-based adventure games?

👾 Before you start…We’ve already covered some gaming ground on the blog so be sure to check other articles when you’re done reading.

- 🎮 The Art of User Interface Design: Gaming and Productivity Tools

- 🏓 Multiplayer Software: From Games to Collaboration Tools

- 🚀 50 Years of Innovation in Video Game Console Designs

Whatever comes next, don’t panic!*

👾 What Is Interactive Fiction (IF)?

Text-based adventure games (more on that in a moment) don’t exist in a void. They belong to a much bigger family of interactive fiction (IF).

According to Jim Maher from The Digital Antiquarian:

“[…] IF is a unique form of computer-based storytelling which places the player in the role of a character in a simulated world, and which is characterized by its reliance upon text as its primary means of output and by its use of a flexible natural-language parser for input.”

Jim Maher, Let’s Tell a Story Together(2)

You can think of IF like traditional books on roids. Instead of merely observing one linear storyline unfold, you’re put in the driver’s seat. You can explore the world, manipulate objects, interact with NPCs (non-player characters)… It’s pure magic!

It’s worth noting that the genre also includes analog entertainment, most notably “Choose Your Own Adventure” books and tabletop role-playing games like D&D.

The Cave of Time, a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book by Bantam Books(3)

Going back to gaming, text-based adventure games—pièce de résistance of interactive fiction—let players roam fantasy worlds using, well…a keyboard.

Just like The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy we mentioned earlier. 👇

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy opening screen via douglasadams.com(4)

Unlike modern 2D/3D productions, most text-based classics don’t have any visuals. There’s no user interface—at least not in the conventional sense—and terminal commands are the only way to interact with the story.

That said, there are a few exceptions…

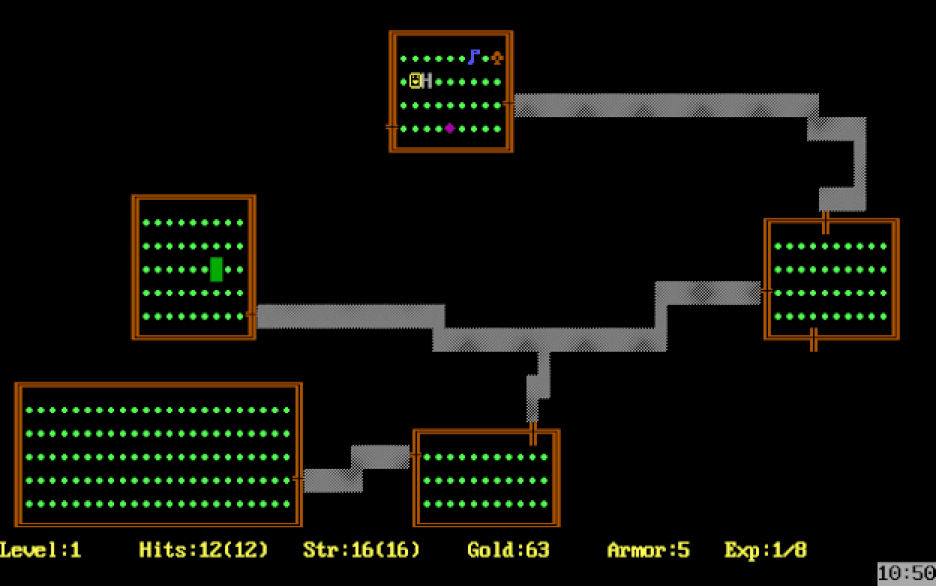

Rogue (1983) by A.I. Design is the grandfather of modern roguelike games.

The game uses simple ASCII art and procedurally generated dungeons.(5)

While the glory days of interactive fiction ended with the dawn of more sophisticated graphical productions, the hobbyist IF community is still going strong.

🥚 What Was the First Text-Based Adventure Game?

The history of text-based games began in 1971 with a programmer, cave explorer, and D&D (Dungeons and Dragons) player William Crowther.

Crowther’s passion for spelunking and a romance with tabletop RPGs became the inspiration for the first text-based adventure game, Adventure.

As Crowther later recalled:

“My idea was that it would be a computer game that would not be intimidating to non-computer people, and that was one of the reasons why I made it so that the player directs the game with natural language input, instead of more standardized commands. My kids thought it was a lot of fun.”(6)

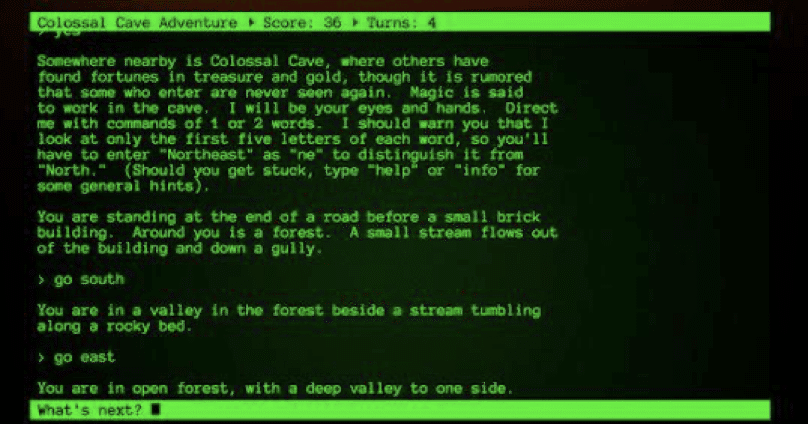

Crowther’s Adventure (a.k.a. Colossal Cave) takes place in a system of caves—based on the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky— a place rumored to harbor treasures, magic, and… well, death of the unweary.

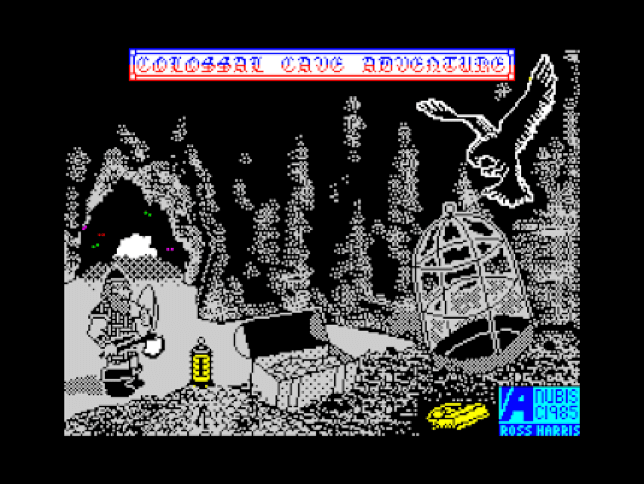

Colossal Cave Adventure by Willian Crowther via Swiss National Museum (7)

Adventure—written for the PDP-10 mainframe computer—was more a fledgling experiment. With Crowther’s consent, other programmers, including Don Woods from Stanford AI Lab, continued developing the game and adding new features.

Over the years, Adventure evolved organically in the public domain until several of its versions saw commercial releases on personal computers.

Colossal Cave Adventure (1985) by Anubis Software via Spectrum Computing(8)

As noted by Jim Maher, a commercial revolution of text-based gaming came in 1979 with Infocom, a software company founded by students and former MIT employees.

“A generation of players learned to see the Infocom label as a guarantee of quality, promising that they would at the very least have a good time with a solid, bug-free adventure game, and that there was at least a chance of finding within a work of real innovation and artistic merit.”(2)

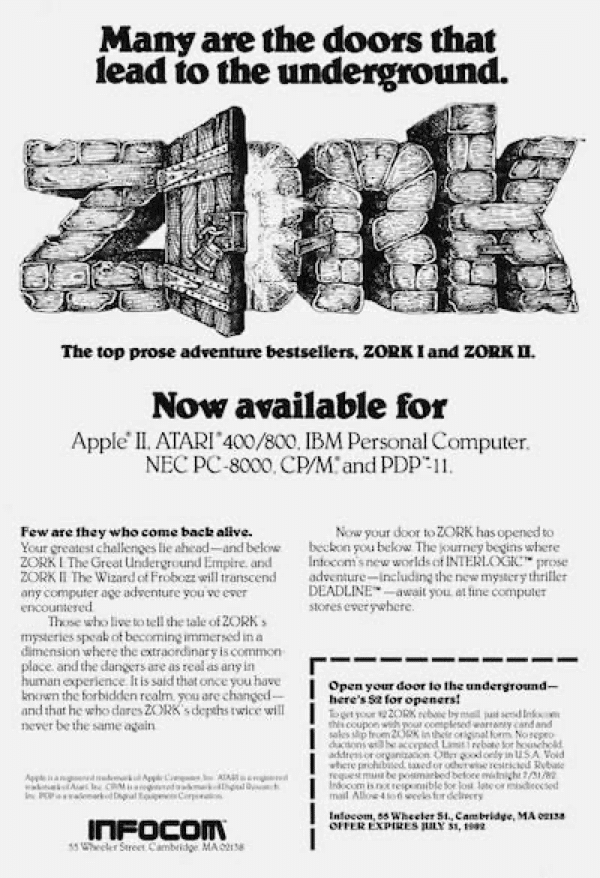

Infocom’s first game, Zork: The Great Underground Empire, introduced many innovative features like more complex natural-language commands (more on that in a moment).

Infocom’s Zork ad via Jason Scott(9)

Following the success of the first game, Infocom released Zork II and Zork III, both of which scored commercial success and contributed to popularizing the genre.

The text-based gaming craze took off for good in the early 80s with many new development studios hoping to jump on the IF bandwagon.

Some noteworthy productions of that period include games like:

- 🛡️ Adventureland (1978) by Adventure International

- 🛡️ Mystery House (1980) by Sierra Entertainment

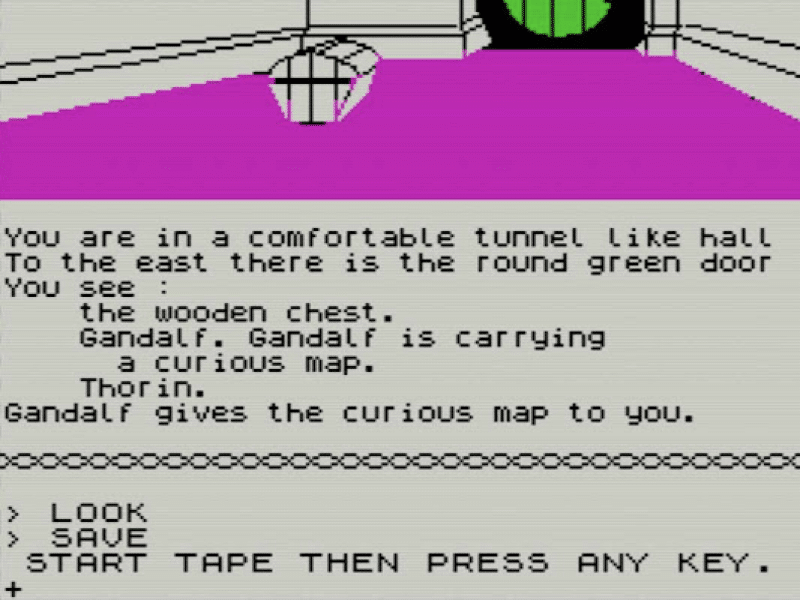

- 🛡️ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1984) by Infocom

- 🛡️ The Hobbit (1982) by Krome Studios Melbourne

- 🛡️ Planetfall (1983) by Infocom

- 🛡️ Time and Magik series (1983-1986) by Level 9

- 🛡️ The Pawn (1985) by Magnetic Scrolls

- 🛡️ Amnesia (1986) by Cognetics

- 🛡️ Leather Goddesses of Phobos (1986) by Infocom

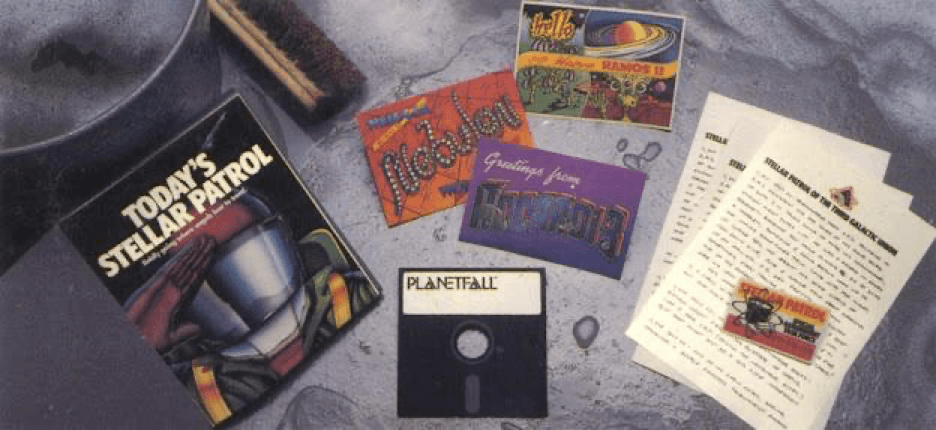

While Infocom closed its doors in 1989, the company made a lasting mark on the industry. The innovative development process, rich narratives, and quality feelies—physical props like maps and documents—made for a quality IF experience.

Planetfall (1983) box contents with feelies via Infocom Elsewhere(10)

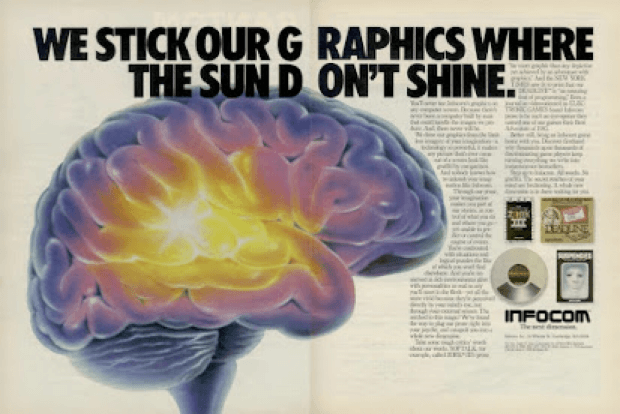

With the arrival of sprites and eventually 3D graphics in the early 90s, the golden era of text-based adventure games lost much of its momentum. The developers’ hard-boiled mindset at the time didn’t help and only accelerated the transition.

“We Stick Our Graphics Where the Sun Don’t Shine” Infocom ad

via The Interactive Fiction Archive(11)

The rest, as they say, is history

⚙️ The Principles of Text-Based Adventure Games

“W. H. Auden once observed that poetry makes nothing happen. Adventure games are far more futile: it must never be forgotten that they intentionally annoy the player most of the time.”

Graham Nelson, “The Craft of Adventure”(12)

Ok, now that we know what IF games are, it’s time for the main course of the day: “How does a text-based adventure game work?”

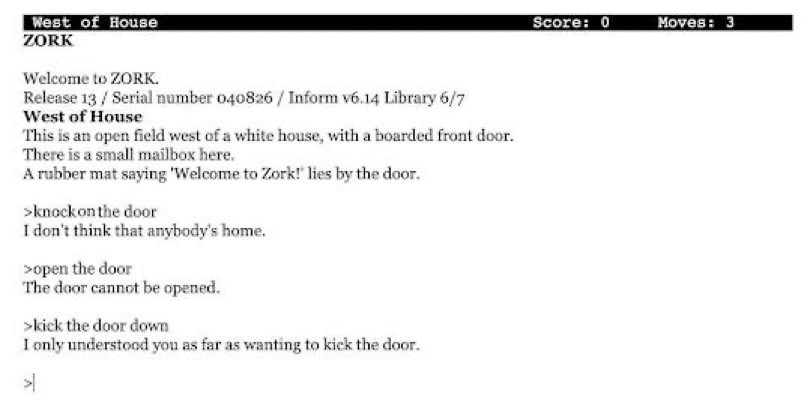

The Parser

The key mechanic that powers IF games is a parser. Parsers transform commands typed in natural language—the language you use for everyday communication—into something the game can actually understand.

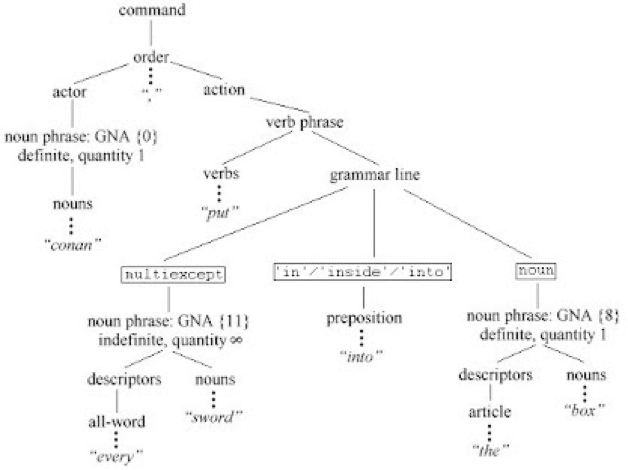

A parsing example from The Inform Designer’s Manual(13)

Communication with IF games is bilateral which means that everything you type elicits some kind of a response from the parser, provided that you know the right words!

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy intro.

Notice the natural-language commands and the parser response

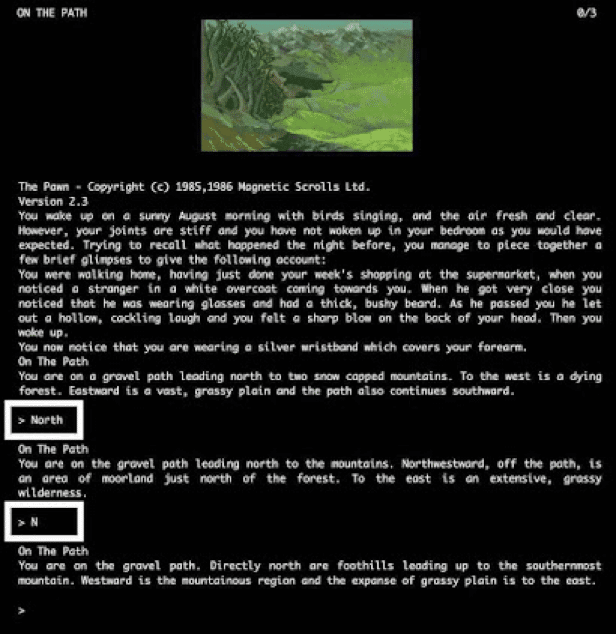

Most IF games, especially the early representatives of the genre, handle simple imperative sentences like “open (the) door” or “examine (the) document.” You can even skip parts of commands for brevity, e.g. “Go South” = “South” = “S.” 👇

The Pawn (1985) by Magnetic Scrolls

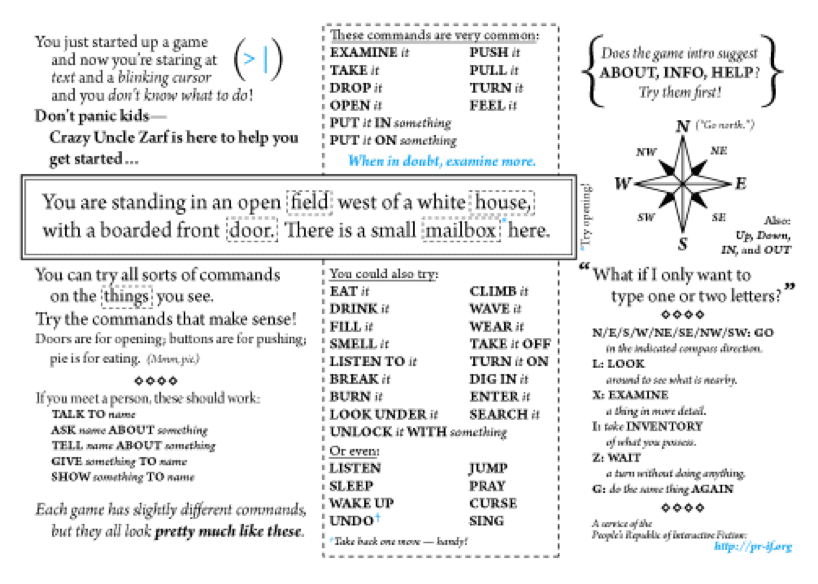

The good news is many text-based adventure games use a set of standardized commands. Here’s a handy cheat sheet you can use to kick off your next adventure.

IF Cheat Sheet by People’s Republic of IF(14)

The complexity of the commands you can use is often limited by the parser itself and the game programmer’s resourcefulness. And this takes us to a classic IF challenge.

Syntax Guessing

Let’s say the game throws you into a dark room—nothing out of ordinary in the IF world—and hints there’s a lamp and a box of matches nearby.

The natural instinct would be to use the lamp and throw some light (put intended) on the situation. The question is, what verb would use to interact with the object?

Take, grab, pick up, fetch… and we’ve barely even started!

Zork (1980) by Infocom

Unless the programmer coded a reasonable number of synonyms, typing a perfectly logical sentence may not yield the expected result.

“Finding out that you needed to flip a switch when you’ve already tried using switch, pull, push and flick can be quite irritating, especially if the game then tells you that you’ve just ‘flicked’ the switch.”

How to Make a Text-Based Adventure: Commands and Parser by H2G2(15)

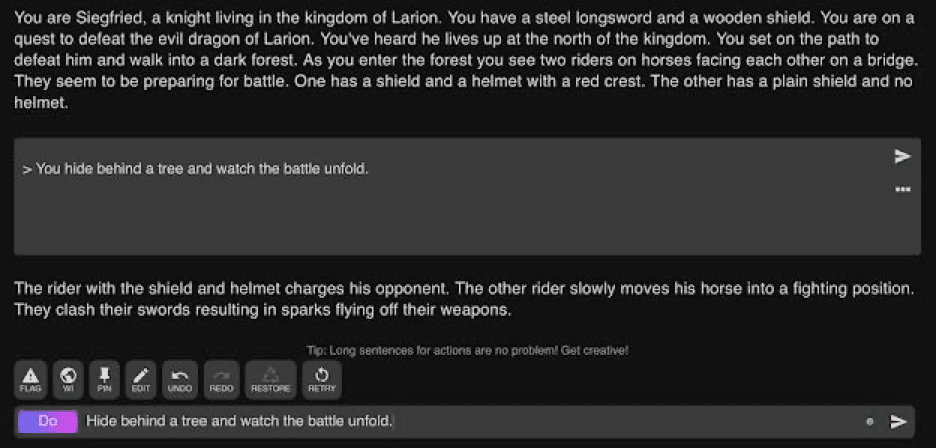

Luckily, a parser’s job is to simplify the input. If the parser is good, it can still “understand” lax commands and return a meaningful response.

AI Dungeon (2019), a modern take on text-based games by Nick Walton(16)

From the linguistic point of view, syntax guessing—even if it results from the game inadequacies—is one of the signature mechanics of text-based adventure games.

Other Key Mechanics in Text-Based Adventure Games

Apart from the technical underbelly, text-based adventure games share a set of qualities that define the entire interactive fiction genre.

Colossal Cave Adventure running on VT100 terminal via Wikipedia(17)

- 🧙♂️ The magic of words. Unlike contemporary 2D and 3D productions, a text-based adventure game doesn’t superimpose the artistic vision of the developer. Instead, whole worlds come to life thanks to rich narratives and imagination alone.

- ☠️ Imminent Death. The IF experience is as unfathomable as it is unforgiving. Death comes often and at the slightest slip-up, effectively adding to other frustrations of the genre. Many IF games don’t even support saving game state.

- ⏳ Pace. Most text-based adventures track time with turns/moves. There’s no time limit for killing the bad guys and saving the princess, at least not in the conventional sense. IF is meant to be digested slowly, one command at a time.

Deadline (1982) by Infocom. A handful of text-based adventure games specify in-game time

- 🏰 Exploration. The lack of visual aids makes IF a hands-on experience. There are no quest markers or interactive maps to guide players through consecutive levels or “rooms.” Each move and command typed into the terminal is a leap of faith.

- ⚙️ Experimentation. Many text-based adventure games make extensive use of puzzles. Prepare for navigating mazes, solving riddles, manipulating switches… As Graham Nelson puts it, IF adventures are “a narrative at war with a crossword.”

All those elements stack up to the irresistible pull and timeless magic of interactive fiction. But they also bring a sea of frustration, especially to novice explorers.

“No matter how much we love interactive fiction, there will still be moments in which we will swear off ever playing such games again. Our favorite games can still bother us enough to make us gently remove the diskette, CD, or DVD on which it came and smash it into teeny tiny pieces.”

Stephen Granade, “Plenty Annoyed” via Brass Lantern(18)

Over the years, the development of interactive fiction theory brought along a number of changes that made the genre more accommodating to beginners.

The Hobbit (1982) for ZX Spectrum with SAVE support

According to Graham Nelson’s “Bill of Player’s Rights,” IF games should balance complexity and playability so that the player can actually enjoy the game.

Here are a handful of rules proposed by Nelson:

- ⚔️ Not to be killed without warning

- ⚔️ Not to be given horribly unclear hints

- ⚔️ Not to need to do unlikely things.

- ⚔️ Not to have to type exactly the right verb

- ⚔️ To be allowed reasonable synonyms

- ⚔️ To have a decent parser

- ⚔️ To have reasonable freedom of action

Nelson’s rules accurately capture the typical pain points of IF players. It’s also a great place to start if you have an itch for creating your own text-based adventure.

If you’re interested in interactive fiction theory, be sure to read “The Craft of the Adventure” collection of essays. You’ll find all the resources linked at the end of this article.

💬 The Power of Storytelling: 3 Lessons for the Future

The simplicity of text-based games combined with the complexity of the English language makes a powerful case for the utility of effective business storytelling.

According to Shawn Callahan, the author of Putting Stories to Work, powerful narratives can sprout from the tiniest and seemingly insignificant anecdotes.

“To inspire at work, leaders must share stories of events big and small. Stories are concrete and specific, so the resulting desire to take action is coupled with a clear example of what to do. It is the antithesis of merely spouting abstractions like ‘Let’s innovate.”

—Shawn Callahan, Putting Stories to Work: Mastering Business Storytelling(19)

Even with more advanced mediums like video and VR, text is still the cornerstone of human interactions. And there are many good reasons for that state of things.

Low Cost and Even Lower Friction

Plain text, especially in a business setup, is the least expensive and technically non-demanding communication channel. You don’t need fancy equipment, custom-made software, or extensive onboarding to send and receive information.

While visuals do help with comprehension, quality narrative—a business memo, team newsletter, or simple email—is more than enough to get your point across.

All those garden-variety formats are perfect for:

- ✊ Motivating your team to take action.

- 🥳 Celebrating small successes.

- 🔄 Debriefing and giving feedback.

- 📈 Driving employee engagement.

- 🤝 Fortifying team camaraderie.

- 💣 Diffusing workplace conflict.

A good testimony to the timelessness of storytelling is the 2019 AI Dungeon, a wildly popular adventure game that generates a unique experience for every playthrough.

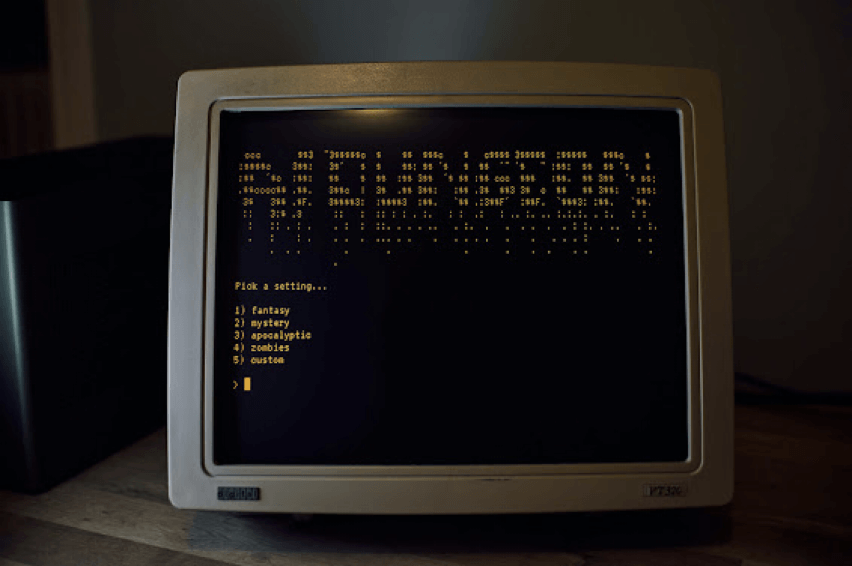

AI Dungeon (2019) running on a DEC VT320 terminal by Eigenbahn(20)

Granted. Walton’s game uses an advanced, pre-trained neural network that’s as sci-fi as it gets, but it does so for the singular purpose of processing text.

And the best part?

Last month, Walton’s company Latitude raised $3.3 million in seed funding, a hopeful sign for the world of “infinite storylines.”(21)

Logic and Structure

While many parser-based games are good at translating natural-language, every action needs to follow a logical sequence.

For instance, you can’t light a fire without gathering twigs and logs for fuel. Pretty basic stuff, right?

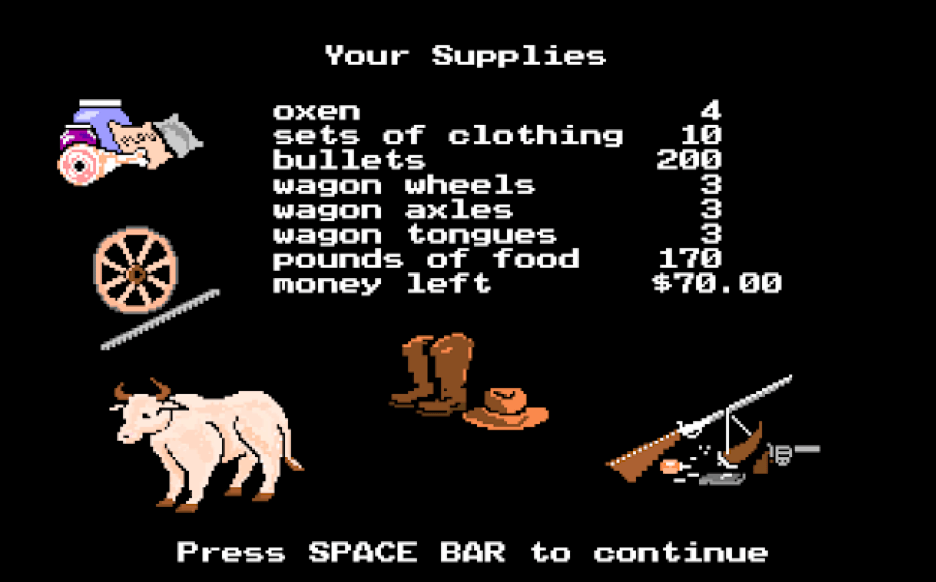

Oregon Trail (1990) by MECC(22)

Written communication—especially when used for giving instructions—requires the same level of complexity, logic, and a dash of consideration to work well.

Throwing inaccurate commands at a parser won’t do any good. The same is true for creating poorly structured team narratives and expecting good results.

“It is crucial that not only your message is clear, but that you spell out what action you expect the reader to take. Do not make them guess. Odds are, they guess wrong. If you want the reader to approve your approach, make sure to say so. Avoid “FYI” messages.”

Practical Guide to Effective Written Communication, PMI(23)

The lesson for today? Effective business storytelling takes consideration, engagement, and time/effort investment. Logic and structure, one word at a time.

Ongoing Experimentation

Want to get into IF? Then you should better prep yourself for a sea of frustration and bouts of disillusionment, at least at the very beginning.

Playing text-based adventure games and actually enjoying them requires time, good instructions, and a whole lot of experimentation.

Dreamhold (2003) by Andrew Plotkin is a stress-free intro to the IF genre

While you can look up common sets of commands used across several parsers, figuring out the unique language of a game is all about trial and error.

“[…] the game world is a world. It has its own logic—whimsy or dream logic perhaps, but still sense. Find the game’s time and reason, and follow it. You will find a way through.”

Andrew Plotkin, The Dreamhold(24)

The more you play the game, the better you get. The more times you die, the more careful and accurate you become with the commands you type into the terminal.

Sounds familiar?

Effective business storytelling is all about figuring out the right, vocabulary, structure, and etiquette for the situation. Every newsletter, email, and chat exchange lets you polish the craft and improve the communication dynamic.

The more you communicate, the better you become at using that magical formula and getting your point across with the least amount of friction.

🐑 Conclusion

While the commercial potential of IF is gone, the vast hobbyist community (not just old-timers!) continues to play and develop text-based games. Forty years after Will Crowther’s Adventure, the magic of plain text is as strong as ever.

The recipe for success?

Absolute simplicity mixed with gripping storytelling and a dash of challenge on top. Consider that the next time somebody tells you the good ol’ art of writing is dead.

“So long, and thanks for all the fish.” 👋

🔗 Resources

- *https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1g84m0sXpnNCv84GpN2PLZG/the-game-30th-anniversary-edition

- http://maher.filfre.net/if-book/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Choose_Your_Own_Adventure#/media/File:Cave_of_time.jpg

- https://douglasadams.com/creations/infocomjava.html

- https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/RHunterGough/20200117/355794/I_Hate_Roguelikes_And_So_Should_You.php

- https://rickadams.org/adventure/a_history.html

- https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2020/01/back-to-the-early-days-of-computer-gaming-with-text-adventures/

- https://spectrumcomputing.co.uk/entry/6099/ZX-Spectrum/Colossal_Cave_Adventure

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/textfiles/3885784383/in/album-72157622111007949/

- http://infocom.elsewhere.org/gallery/planetfall/planetfall.html

- http://mirror.ifarchive.org/if-archive/infocom/adverts/ad1.jpeg

- http://www.ifarchive.org/if-archive/programming/general-discussion/Craft.Of.Adventure.txt

- https://www.inform-fiction.org/manual/about_dm4.html

- http://pr-if.org/doc/play-if-card/play-if-card.html

- https://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A20600641

- https://play.aidungeon.io/

- https://pl.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:Colossal_Cave_Adventure_on_VT100_terminal.jpg

- http://brasslantern.org/editorials/annoyed.html

- https://www.amazon.com/Putting-Stories-Work-Mastering-Storytelling-ebook/dp/B01B6R8LME

- https://www.eigenbahn.com/2020/02/22/ai-dungeon-cli

- https://techcrunch.com/2021/02/04/latitude-seed-funding/

- https://archive.org/details/msdos_Oregon_Trail_The_1990

- https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/practical-guide-effective-written-communication-7828

- https://eblong.com/zarf/zweb/dreamhold/help.html

The Rise and Fall of Skype: A Journey Through Its History

The Rise and Fall of Skype: A Journey Through Its History  A Review of Notion and The Powerful Rise of No-Code Project Management

A Review of Notion and The Powerful Rise of No-Code Project Management  What Is Web3? It’s More Than Just Crypto Companies: The Powerful Rise of Web3 Startups Explained

What Is Web3? It’s More Than Just Crypto Companies: The Powerful Rise of Web3 Startups Explained  The History of Markdown: A Prelude to the No-Code Movement

The History of Markdown: A Prelude to the No-Code Movement  History of the To-Do List and How to Get Yours Organized

History of the To-Do List and How to Get Yours Organized  A Review of Zapier’s History: Rise of The No-Code Movement

A Review of Zapier’s History: Rise of The No-Code Movement